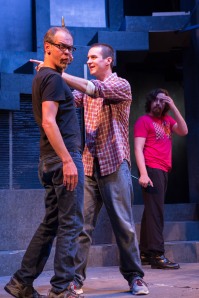

Louis Butelli (left) gets some choreography down in rehearsal with fight director Casey Kaleba, and actor Joe Brack looking on. Photo by Teresa Wood

Hi again from your pal Louis Butelli. Here at Folger Theatre, we are coming to the end of our rehearsal period for Robert Richmond’s production of Julius Caesar, and are preparing to enter technical rehearsals, lovingly known to theater practitioners as “tech.” I’ll say more about that at a later date. Meanwhile, our first preview is rapidly approaching, and we hope you’ll come see us. Click here for your tickets.

For now, though, we are about three weeks into living with this play, its characters, scenes and relationships, and we continue to experiment with how best to tell this story in the year 2014. Some of what we have so far is compelling and beautiful, complex and chilling, and very, very exciting. Some of what we have so far, at this stage of the game, is just confusing.

Let me clarify. Of all of Shakespeare’s plays, Julius Caesar is one with which a very large proportion of any audience will be familiar, to one degree or another. The play continues on as a tent-pole in the study of literature, as it has for decades if not centuries. It has a whole raft of famous lines – “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves,” “Beware the ides of March!” “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears!” “It was Greek to me,” “Last but not least in love,” “Et tu, Brute,” – and we all know that the play ends with a pile of dead bodies, and that Mark Antony gets a sequel. With this perceived familiarity, we are discovering, comes the idea that all of us, both the artists working on it and the audience that will come to see it, “already know” this play.

Having spent the past three weeks trying to focus the play into an evening’s entertainment on Capitol Hill (for which you can buy a ticket here), I can tell you that I, for one, did not know this play as well as I thought I did. Please feel free to insert a joke about learning lines here.

My point is that Memory – that thing upon which senses-of-self, personal relationships, communities, cultures, nations, and history itself is built – is fundamentally an adaptive and malleable thing. I won’t say that it’s entirely faulty, but I will say that Memory does consistently seem to prove itself a highly selective thing. Ask a braggart at a bar, a candidate for elected office, anyone with aging parents, or a young child caught with her hand in a cookie jar.

Still, I’ve been thinking quite a lot about how Memory functions in the play itself:

-On October 28, 2014, your author Louis Butelli, will stand on stage at the Folger Theatre, down the street from the Supreme Court and the US Capitol, to play in Julius Caesar.

-In 1599, or thereabouts, an Elizabethan poet and playwright called Will Shakespeare presented his play about the murder of one Emperor and the ascension of another on-stage in London, conceivably in the presence of an Empress.

-On the 15th or “ides” of March in the year 44BC, the title character of the play was murdered on-stage at the Senate in Rome.

History is already telescoping in on itself!

To go a little further for a second, if you can stand it: I’ll be playing Cassius, a real-life historical personage himself (born 85BC – died 42BC). In Act I, scene 2, of Julius Caesar, as he is laying out his case for murder to Brutus, Cassius has a speech (click here to read) wherein he discusses an impromptu swimming match with Caesar. The two men jumped into the river Tiber and, halfway across, Caesar could go no further, and Cassius dragged him out of the water. In relating the episode to Brutus, Cassius says:

“I, as Aeneas, our great ancestor, did from the flames of Troy upon his shoulder the old Anchises bear, so from the waves of Tiber did I the tired Caesar.”

Without getting too crazy about it, I’ll just point out that Anchises was a figure from Greek mythology, known mainly for having an affair with love goddess Aphrodite who subsequently gave birth to his son Aeneas. The two men were relatives of King Priam, and are mentioned in Homer’s Iliad, wherein the son hauled his father away from the carnage of the Trojan War on his shoulders.

Things get weirder with Aeneas. He, as a fierce opponent of the Greeks, was transformed into the hero of Virgil’s Aeneid, the original hero of Rome. Julius Caesar later claimed lineage to Aeneas, and to Romulus and Remus, the twin children, born of gods and nursed by wolves, who created Rome itself.

This is getting complicated.

To re-cap more simply: actor in 2014 delivers lines written in 1599 spoken by a character from 44BC making reference to events that, if they actually happened at all, happened sometime around 1200BC.

And lest you think that this Memory trick only works in reverse…

In 2012, a writer and Internet personality called John Green published a novel for Young Adult audiences. The story concerns a teenaged girl dying from cancer, her relationship with a teenaged boy named Augustus (note the name), and what it is to be remembered in writing. The book was a New York Times #1 bestseller, and was adapted into a Hollywood film that has grossed, to date, over $300 million. The name of the book?

From the earliest human cave painters, to the builders of the pyramids, to the Homeric bards, to the rise and fall of Rome, to William Shakespeare, to, dare I say, the Internet age, we are driven to remember, and we look back on ourselves again and again, for better or for worse.

Julius Caesar is about many things: but it is most certainly about Memory. Click here now to come and see our show!

Louis on Twitter: @louisbutelli

Stay connected

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.